"Tolstoy" by Sid Sackson (Excerpt from "Beyond Words")

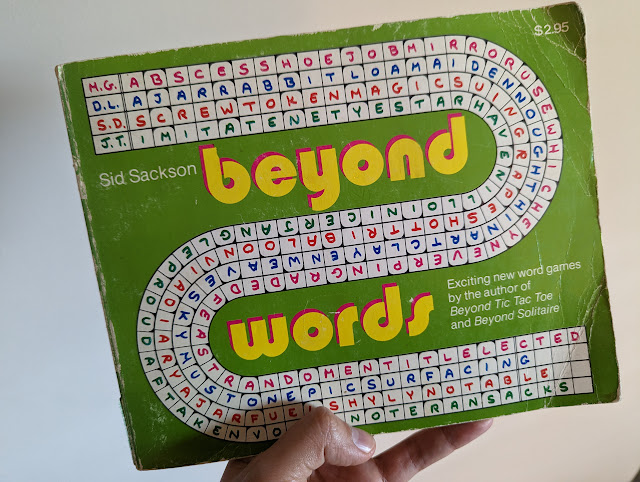

Cleaning out some old office furniture, I stumbled across a cache of vintage game books I purchased from Dickson Street Books many years ago. Among the collection is this well-loved 1977 edition of Beyond Words by Sid Sackson, the legendary designer of Acquire and Can't Stop.

This was the third in his series of "Beyond" game books, the first two being Beyond Tic Tac Toe and Beyond Solitaire. This book contains six word- and letter-based games named in honor of famous writers. The book presents short rules for each game, followed by perforated sheets that you were meant to pull out and play on with pencil or pen. Kind of a crossword or word jumble book you'd find in a supermarket checkout.

The first of these games is titled "Tolstoy," which I share below.

First, some historical notes if you've never read rules by Sackson. I've often considered Sackson's designs years ahead of his time, yet I still get tripped up by how he writes his rules. I can't tell what is just 50+ years of linguistic drift, restrictions of 1970s print publication, or just idiosyncrasies of Sackson's writing style. Some examples you'll notice:

- He calls "Preliminary" what I would now call "Setup."

- He uses third-person male pronouns where I'd use second-person pronouns.

- He uses passive voice where I'd use declarative sentences.

- He uses em-dashes and embedded clauses where I'd advise shorter, simpler sentences.

- He uses only one diagram, where I would have used a series of diagrams.

- He doesn't label the cities on the board, he only using stars.

TOLSTOY

2 Players

Named in honor of Leo Nikolaevich Tolstoy (1828-1910), author of War and Peace, because both the book and the game are based on Napoleon' invasion of Russia.Object.

For the "French" player, to move into Russia by forming words to capture Odessa, St. Petersburg, and Moscow — and to escape to the border. For the "Russian" player, to stop this from happening by using letters the invader needs.

Preliminary.

Carefully cut or tear the sheet along the dividing line into two halves. Each contains a field of triangles, some empty, some with letters, and three with stars. (The triangle with three stars represents Odessa, lour stars represents St. Petersburg, and five stars represents Moscow.) The boxes at the left are for keeping score, and the circles at the right indicate letters that earn bonuses.Each player takes one of the fields and using a black pencil or pen, writes in the letters of the alphabet in twenty-six of the empty triangles. When the letter Q is written, add a u next to it in the same triangle. The fields are exchanged, and the players write in another alphabet in the remaining twenty-six empty triangles. (When the letters are being filled in, a player doesn't know which side he will be playing with that field, so the letters should just be placed at random. And if by mistake a letter is left out or is used an extra time, it doesn't really matter.)

Either of the two fields is picked for the first round of the game. Then who will be the French player is determined by tossing a coin, or in any other convenient manner; the other player is the Russian. In the second round, with the second field, the players reverse roles.

How to Play.

The French player secretly decides in which of the five triangles—numbered from 1 to 5—he wishes to start his invasion. At the same time the Russian player secretly chooses one of six triangles—numbered from 6 to 11—from which to start his defense. Using differently colored pencils, each player draws a circle around the letter in his chosen triangle and lightly colors in the entire triangle.[In the illustration, showing part of a field, the French player—blue—has chosen triangle 1 and the Russian player—red—has chosen triangle 8. The coloring of the other triangles will be explained shortly.]

The French player plays first. Starting with a letter in a triangle next to—either along an edge or at a corner—his original triangle, he forms a word of at least two letters, each letter being next to the previous letter. The letter in the original triangle is never used as part of the word. The triangles used are colored and the last letter is also circled.

[In the illustration, the French player makes Qu-I-P as his first word.]

The Russian player then forms a word in a similar manner.

[In the illustration he makes the word N-A-I-L]

The players in turn continue by forming words, starting with a letter next to the last letter in the previous word. Colored triangles may not be used again by either player.

In order to occupy a city (triangle with stars) the French player must end a word on that triangle. He may use the starred triangle as any letter he wishes.

[In the illustration, the French player makes Y-O-U as his second word, occupying Odessa.]

The Russian player is not allowed to enter any of the three cities. He is also not allowed to enter any of the seven "border" triangles—the five triangles numbered from 1 to 5 and the two triangles directly above them.

The round continues until the French player either reaches the border—by ending a word on one of the seven. border triangles—or until he can no longer form a word. If the Russian player is unable to form a word, the French player continues alone until the round is ended.

Scoring.

Only the French player scores. He scores one point (one box in the scoring area) for each word he forms. For each J, Q, X, or Z in a word he scores one bonus point.[In the illustration, the French player scores two points for Qu-I-P: one point for forming the word and one point for using the Q, a bonus letter.]

If the French player occupies a city by using that triangle as a bonus letter, he does not score a bonus point.

When the French player occupies a city he scores as many points as there are stars in the city—in addition to the point for forming a word.

[In the illustration, the French player scores four points for occupying Odessa—three points for the stars in the triangle and one point for Y-O-U.]

If the French player ends the round by reaching the border, he scores again for each city he occupied.

[For example, the French player occupies Odessa and Moscow and then returns to the border. He scores an additional eight points. If he returns to the border without having occupied a city, he receives no extra points.]

Winning.

After the two rounds are completed, the French player with the higher score is the winner.

Hi, it's me Daniel again here in the 2023. If you like this sort of article and want to support more of this work, drop a buck at https://www.patreon.com/danielsolis. Thanks!

Comments

Post a Comment